Mrs. Korthaus taught me everything I needed to know, even before I had students of my own

Lessons Beyond the Textbook: How One Teacher Inspired Me to Be Great

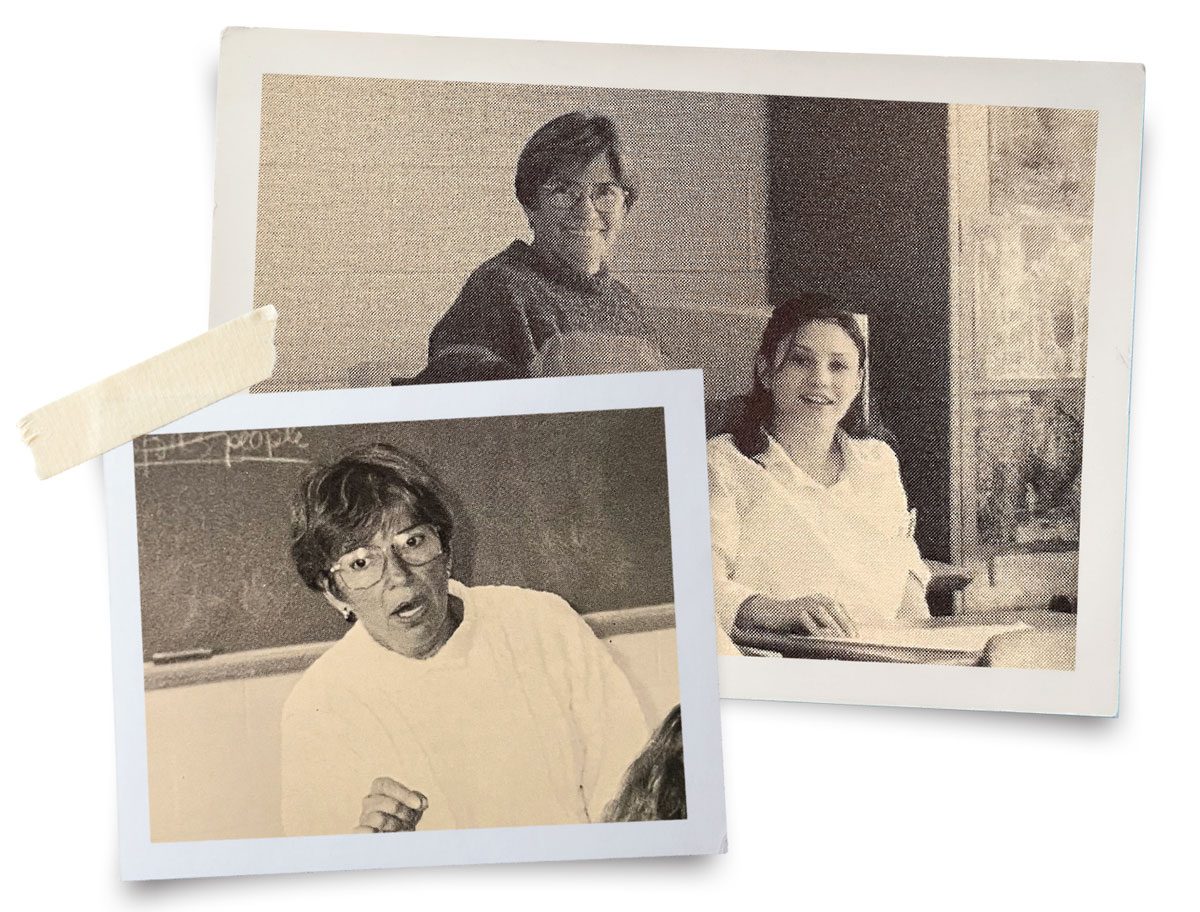

I was 14 when I met a firecracker of a soul, a bombastic professor of life with colossal charisma who stood all of 4-foot-10. Mrs. Korthaus was the beloved English teacher at our rural Pennsylvania Catholic high school. She hadn’t married until she was almost 40, and hadn’t become a teacher until her husband’s job brought them to our industrial town, where there weren’t many careers for women.

In the 1990s, we subtly noticed that her years in corporate life, being financially independent, had given her a sense of fearlessness that she transmitted to us. She gave me an unjudged ground to tumble through young mistakes and learn, by trial and error, who I wanted to become—who I could become.

Get Reader’s Digest’s Read Up newsletter for more real stories, fun facts, humor, cleaning, travel and tech all week long.

The kind of woman I want to be

As much as she taught me about literary works and journalism, knowledge I would take into my career as a writer and the lead editor of the Reader’s Digest sister site TheHealthy.com, I also studied the way she made the world better and herself happy. I’d never known a female so self-propelled.

A small town has a way of making a girl’s whole world small. When it came time to decide where to go next and what to do for the rest of my life, I found it tough to imagine what was “out there,” and even tougher to know what was inside. Of me. Sure, I performed well in school, but I wasn’t genuinely invested in my potential—in fact, I feared success. A career seemed scary. If I’d had my way back then, I’d have chosen to stay right where I was for the rest of my life. It was a blessing that I didn’t get my way. Mrs. Korthaus had an important part in that.

If Judge Judy had taught Shakespearean comedy or Dr. Ruth had coached the golf team, then you can imagine Mrs. Carol Korthaus. She’s known for her chiseled cheekbones and plainspoken thoughts; her larger-than-life, exclamatory mannerisms; and a joy-filled spirit not unlike Oprah’s old holiday gift giveaway episodes: “YOU get an A, and YOU get an A!”

Her students went to her when we were applying to college, seeking the kind of teacher who would give a thoughtful recommendation letter. Our reliance on her was a testament to her gift for helping us see the good in ourselves when we hadn’t yet learned to find it in the mirror. Mrs. Korthaus made writing, literature and communications a window to the world for kids who didn’t realize how sheltered growing up in a small lakeside town in western Pennsylvania had made us. The multiple extracurricular activities she helmed—producing the spring musical, leading the mock trial team, coaching golf and tennis, overseeing the prom committee and emceeing the school’s annual fundraising auction, just to name a few—showed us a woman fulfilled by her passions.

Standing on a chair to make her point (and, I suspect, for a full view of the classroom), she’d cry, “The hu-MAN-uh-teez!” as her pointer finger would poke holes in the thin air above her, like Braveheart declaring the Battle of Stirling. To her, the humanities were those subjects that showed students the dignity and goodness within every human, the inherent need to feel worth—in ourselves and others.

She didn’t have to demand that we listen; she inspired us to pay attention with the way she herself radiated a joy of learning. She was committed to noticing every student, really seeing each of us, which is why many of us did so well in her classes—and beyond. She knew that a child’s behavior reveals the difference between one who feels loved and one who doesn’t.

Back to the classroom

All this is why, more than 25 years after I graduated from her classroom, after I had moved away for a writing career, then moved back again, I still think of myself as her student. And, why, with her clearly in mind as my role model, I answered an unexpected call.

“We need an English teacher ASAP.” It’s a text from my friend’s mom who sits on a board for the local community college. “Would you have any leads on someone who may be interested?”

Days later, I’m handing out the fall syllabus I’ve just written to 40 new faces who, for the next four months, will be my students in Introduction to English. Some seem enthusiastic; others, apathetic, exhibiting levels of commitment that are differentiated by signals like their eye contact and smiles (and the couple of yanked-up hooded sweatshirts that suggest they’d rather be left alone), how far back in the room they’ve selected a seat, the energy with which they take notes, and, of course, their participation.

At the end of our first class, a few of them nod and a handful grin, in what appears to be their initial approval of me when I’m able to go around the room with each of their names memorized.

The college offers two-year degrees in nursing and manufacturing trades, and the English course is part of their core requirements … so in other words, the communication of thoughts and emotions through literature and the media appears to be a natural passion for only a few.

The first week, I tell them that it’s safe to share only as much about their lives as they feel comfortable doing, and that I’ll never discuss the background they cover as part of the assignments unless they share it in front of the class first. I quickly note that almost all of them have jobs—at a factory, a grocery store, a hospital—and I pledge to myself not to make their lives more jam-packed with stress and work than they already are.

The state body that accredits the college requires that the curriculum has to cover a broad range of genres—we’re talking medieval literature to ’80s sci-fi and fantasy to news and current events—with lessons on grammar, syntax, comprehension and composition structure. I don’t know what would happen if I don’t cover all those bases, but the dean’s son is in my class, which is one reason I don’t intend to find out.

In my mind, I pledge that if I can send every student into finals with the confidence to write a thoughtful, correctly spelled and technically accurate cover letter and résumé, then I’ll have served them successfully. “No matter which industry you go into, good writing stands out,” I often tell them. Show, don’t tell, I remind myself, but when I tell stories from my own career, very few of them seem at all impressed. I work to earn their trust with every lesson.

An unexpected connection

As the weeks progress, I come to sense what it’s like to be the instructor some students are drawn to without reservation, what it means to meet students who have given up on having much faith in authority, and what it is to see students struggling through a situation they believe no one could pull them through even if they were open to it.

There’s the boy who approaches me with curiously knowing eyes on the first day of class. “Are you related to the family who owns the factory in the middle of town?”

“Yep,” I tell him. “My grandpa started that. All the guys in my family work there.”

“My dad has worked for your family my whole life,” he says. We stand there regarding each other for a minute—him almost seeming to say, Your family has provided for me, as I want to tell him, Yours has provided for me too. From that moment on, there’s a subtle feeling between us that we, too, are related. There’s the young couple who always sit in the back—well, he always sits in the back, and often takes notes and assignments home to his wife, who seldom attends. As he explains to me in the second week, she struggles severely with her mental health.

There’s the student who wears a hoodie cinched tight around his eyes and jokes to the class about his past stealing cars, but hands in assignments that show me he needs an outlet to express how he’s always felt underestimated and overlooked. I let him have the floor as much as he wants it, hoping he can feel that I see his capability. There’s the young woman who comes looking polished, takes careful notes, and in a small-group discussion shares why she is her grandfather’s caretaker: because he rescued her and her dog from an abusive home. She’s studying science to go into nursing, though I can see how romanced she is by stories.

There’s the mom of three who works the night shift as a medical assistant in the hospital’s neonatal intensive care unit. She’s trying to get through the nursing program because she wants to help kids, like the teams that helped her teen son, who battled leukemia before he passed away last year. Many of her assignments focus on stories about him, and at times I have to ask the class to excuse my tears. Sometimes she nods off in class from the exhaustion of studying, working and raising two younger kids, but even when a snowstorm hits toward the end of the semester, she’s present and smiling every day.

Through what they share in class and in the context of their assignments, my students let me into their worlds—their families, their pasts, their hopes. The boy whose dad works with my family is a wholesome spirit, and I can’t tell whether he’s such an active participant simply out of respect, or because he’s genuinely curious about pursuing something related to this field. The way he talks about his dad and grandpa, I imagine he’ll spend his life close to home. While we have this time together, I try to fill the room with ideas that make his eyes flash with interest.

You deserve an A

Over the semester, we do drills of rules like how to distinguish it’s from its, and there, their and they’re. On Halloween, we play Mad Libs on the dry-erase board with candy as the prize. The former “free car” enthusiast surprises me by leading the class in an in-depth explanation of a full-length fantasy work that’s a revelation of his comprehension. My students sometimes wince at assignments, but only a couple of times do I need to chat with someone about a late deadline.

“I don’t know what you’re doing in there,” the dean says, in a way that startles me, until she continues: “My son came home last night and said, ‘Mom, I’ll be in my room. I need to write 750 words for English.’ He’s the youngest of all my sons, and I’ve spent his whole life riding him to do his homework. I have to thank you. I think you’re getting through to them.”

We write stories. We read stories, so that one reader will feel less alone in their hurt. Their conflict. We teach to make sure an individual just knows that these resources of compassion and shared experience exist. If we’ve done our job, the student is left with an inextinguishable willingness to search for them. The only students who don’t get A’s are the few who blatantly disregarded the maximum of three absences without any explanation. The husband who reports in for his wife gets an A … for them both. I struggle with how to handle it, but finally decide I don’t want to be the reason she gives up. If anything, I figure, she deserves an A for the loyal and caring husband she chose.

My highest score

I’m invited back for a second semester, teaching both English and communications. I accept, even though my evaluations from the students at the end of the semester—my report card—contain their critical points. A few scored me low for not always starting class on time. They don’t realize that I, too, have a lengthy commute on back roads, sometimes in bad weather. That I’m sometimes rushing out the door after developing lesson plans and grading essays and projects in addition to the work I had on my plate before I started here, because if I really kept track of all the hours I spent preparing lesson plans and grading their papers, I’d be earning less than minimum wage. I’m learning that these are costs that educators don’t count. I’m giving my students my best work, just as I aim to do with everything I take on.

Most teachers probably recognize that we’ll never please them all … but as I scan the rest of the report, there’s the grade I really wanted to see: I feel that this instructor cares about me. It’s my highest score.

At the end of the semester, the mom who lost her child to cancer hands me the final yearbook photo of her son, taken four months before he passed. I pin it above my office desk at home, understanding it’s as if she wants me to know that I’ve been teaching them both.

I believe I treated all my students with the same approach—at least I meant to—but there are a few who managed to stand out. They’re the students who, even in their own very quiet ways, were open with me about the struggles in their life, who were there out of their commitment to work toward an easier path, and who let me in, trusting that I would be part of their solution. The ones who believed—whose hearts were still trusting enough to believe—that I cared. Mrs. Korthaus showed me: That’s the real success of being a teacher.

This is an excerpt from Show, Don’t Tell: A Writer, Her Teacher, and the Power of Sharing Our Stories.

Why trust us

At Reader’s Digest, we’re committed to producing high-quality content by writers with expertise and experience in their field in consultation with relevant, qualified experts. We rely on reputable primary sources, including government and professional organizations and academic institutions as well as our writers’ personal experiences where appropriate. This piece is an excerpt from The Healthy‘s senior editor Kristine Gasbarre Qaderi’s latest book, Show, Don’t Tell: A Writer, Her Teacher, and the Power of Sharing Our Stories. We verify all facts and data, back them with credible sourcing and revisit them over time to ensure they remain accurate and up to date. Read more about our team, our contributors and our editorial policies.